Edward Atkins as a student

About the Author

Edward Atkins grew up in Montclair, N.J., and was attending Newark Academy in September 1939, during the beginnings of World War II. He earned the Eagle Scout Badge with Bronze Palm and graduated in June 1944, when the the invasion of Europe started.

It was during these five years of international tumult of a scale unknown to mankind that Atkins enlisted in the navy. Just out of boot camp, he was assigned to the U.S.S. Antietam and served on the flight deck for two years.

Following his service, Atkins graduated from Yale University with a degree in business administration. He worked in New York City banks and electronic companies, and earned an electrical engineering degree.

He went on to a position with a company managing the Polaris Missile System for the U.S. Navy. This led to a job as a management engineer with the U.S. Navy Electronic Systems Command in Washington, D.C., until his retirement in 1991.

Atkins' outside interests centered on robotic devices and computer applications to develop neural networks in medicine, maintenance, decision-making, and other "If-Then" problems.

More recently, he compiled this book — "On Which We Serve: Where Life-Lessons are Learned" — in two parts.

Edward Atkins in the navy

From the Author

Upon leaving the Navy Department in 1991, I devoted most of my time to working on my hobby of automatic controls, as presented by the Galil Motion Control company. In so doing, I developed a course of study for electrical engineering grad students. I also created a website for the course, part of which appears in this motion control demo. Automatic controls kept me occupied until about 1997, when I set this activity aside so that I could devote all my time to creating the book, "On Which We Serve: Where Life-Lessons are Learned," seen in this website.

In so doing, I developed a course of study for electrical engineering grad students. I also created a website for the course, part of which appears in this motion control demo. Automatic controls kept me occupied until about 1997, when I set this activity aside so that I could devote all my time to creating the book, "On Which We Serve: Where Life-Lessons are Learned," seen in this website.

Now, after too many years trying to market my book, I have reverted back to my real interest: the application of fuzzy logic to problems, especially automatic control systems. I accomplish little that is worthwhile but I enjoy the time spent on this subject. It's a fascinating one. If nothing else, doing this defines what learning is all about: having a passionate interest in the subject being learned. This is a "Lesson Learned" that's "solid gold." You can see a very small result of this by turning to pages 758-759 of "On Which We Serve, Part 2."

Edward Atkins, 1995

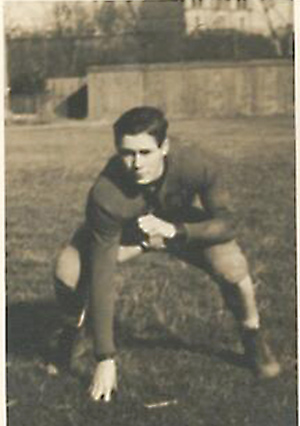

Newark Academy, 1943 & 1944. Yes, we had a good two seasons, in large part because our captain, Toni Minisi, was outstanding: he was a star at the Naval Academy in 1945 and an All-American at U of Pa. the next year. Hold on to your hats: In those days the Ivy League was THE football powerhouse. We played the single-wing (more intricate than nowadays), we played both offense and defense, we wore leather helmets, we had no face masks or mouth guards, we had to block using only our shoulders (NO hands) and we played in front of no spectators (we were isolated). Otherwise, that time was a legitimate precursor to today's football.

Newark Academy, 1943 & 1944. Yes, we had a good two seasons, in large part because our captain, Toni Minisi, was outstanding: he was a star at the Naval Academy in 1945 and an All-American at U of Pa. the next year. Hold on to your hats: In those days the Ivy League was THE football powerhouse. We played the single-wing (more intricate than nowadays), we played both offense and defense, we wore leather helmets, we had no face masks or mouth guards, we had to block using only our shoulders (NO hands) and we played in front of no spectators (we were isolated). Otherwise, that time was a legitimate precursor to today's football.

Oh yes, we also made tackles around the hips/legs. None of the predominate "bear hugs" of today. I'll only add that the photo showed a stance appropriate to both defense and offense (tackles did a lot of "pulling"). In sum, football does have its merits: hard work, dedication, self-discipline, persistence, losing, But most of all to me, teamwork was the main attraction of football. No other sport has that quality to the extent that football does. None. Unless each and every player does his part well the result will usually be of no avail. That's teamwork.

Note, a funny anecdote: During the 1943 season I was a tackle (the 1942 season I was an end). I was opposed by their guard and tackle. On this particular play their offense was going to double-team me At the snap, I stiff-armed their shoulders and for some reason they were both flattened, lying flat on the ground (maybe purposely). This caused me to be crouching low to the ground. And yes, their play was designed to go right where I was. Well, their ball-carrier saw the situation and decided he could huddle me. Which he did. Since my job was to stop him from gaining ground I did the only thing available: I quickly raised up with the intention of stopping the runner with the top of my helmet. But I was too energetic and the consequence was my nose stopped the runner. He fell head over heels over me, having gained about one yard. I immediately checked that my nose had no adverse effects. As the ball carrier got up and trotted back to his huddle he said, without stopping, "Are you OK, Eddie?" (We knew each other casually since I was from Montclair and we were playing Montclair Academy). I laughed as he trotted by. I thought it was "funny" that I had "done this deed."

In those days was not a matter of that much concern: It was a game, to have fun and keep it relatively light. Life has too many other more important activities, although sports in general are useful.

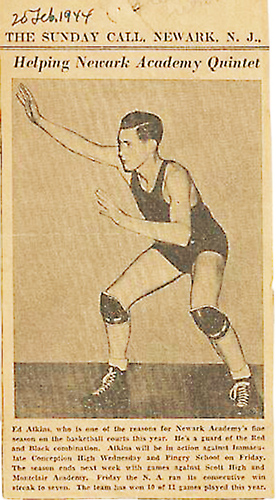

Yes, we also had a good basketball team record. The play was somewhat different in that there was no dunking (there were no "beanstalks" in those days). While I don't watch much basketball ("you've seen one you've seen them all") I don't believe they use the "give and go" very much. And I don't know why they eschew the underhanded pass on occasion. Waving the ball over your head merely says"here it is."

Yes, we also had a good basketball team record. The play was somewhat different in that there was no dunking (there were no "beanstalks" in those days). While I don't watch much basketball ("you've seen one you've seen them all") I don't believe they use the "give and go" very much. And I don't know why they eschew the underhanded pass on occasion. Waving the ball over your head merely says"here it is."

In fact, an underhanded pass in football would be a good idea; no one in the defense's backfield would know where the ball is. Anyway, back in the old days we used a two-handed set shot from outside. This provided the opportunity to once in a while start such a shot which would cause the defender to leap in the air to block the shot. It also presented the neat opportunity to pull the ball down and dribble on past that defender, thus setting up two-on-one situations.

It's the same in football: the quarterback goes through the FULL motion of throwing the ball, thus getting the rushers off their feet which allows a mobile quarterback an opportunity to cause havoc down field.

Well, enough of my 2 cents worth. — Edward Atkins